The devastation that World War II brought upon Poland was colossal. Particularly in Warsaw, the capital city, the war left behind a sea of ruins. This destruction presented an enormous challenge - but also a unique opportunity for architects to participate in the city's rebirth, creating a new architectural landscape from the ashes. However, these years were also marked by tension between Poland's pre-war Modernist legacy and the official architecture of the time, Socialist Realism.

This tension is particularly apparent in the work of Helena Syrkus and her husband Szymon. The couple were major proponents of Modernism and had a substantial impact on Poland's pre-war architectural landscape. Post-war, they found themselves grappling with the new socio-political conditions while aiming to continue their modernist design principles.

A notable example of their work is the housing estate for the Warsaw Housing Cooperative at Kole, built between 1947 and 1950. This project represents a fascinating blend of pre-war Modernism and the realities of post-war reconstruction. Rising on pillars, the houses in this estate provide innovative and practical living solutions with duplex apartments, bright interiors, and the novel use of space.

However, the estate, with its clear references to Modernism and functionalism, quickly fell foul of the authorities of the time. The new political regime favored Socialist Realism, an architectural style that was distinctly different from the avant-garde principles the Syrkuses adhered to. Consequently, the couple faced criticism for their design approach at Kole and the contemporaneous Praga I housing estate in Praga North, leading to a self-denunciation of their prior architectural works.

Despite this, today the Kole estate stands as one of Warsaw's most beautiful and well-planned developments. Its modernist elements—like the perforated entrances to buildings, the glazed entrance halls decorated with mosaics, and the galleries along some buildings—continue to charm and inspire. These are living symbols of the enduring power of Modernism, even in the face of political pressure.

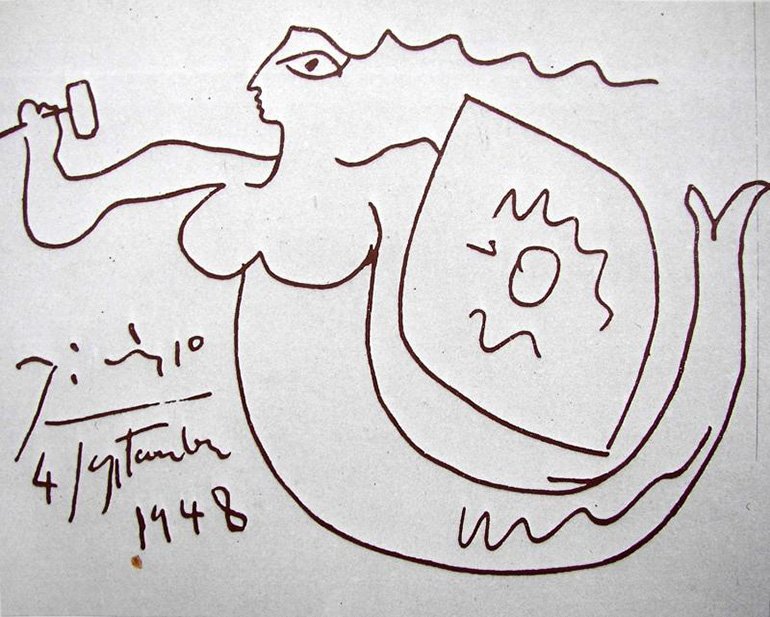

A poignant testament to this estate's historical significance is the visit of Pablo Picasso in 1948. He was particularly moved by the use of rubble concrete formed from the ruins of Warsaw—an innovative construction technique used for the first time. Picasso spontaneously painted the Warsaw Mermaid in one of the apartments, a painting that eventually drew hundreds of visitors and added to the estate's historical and cultural significance.

In conclusion, the influence of World War II on Polish architecture is a complex narrative of resilience, innovation, political conflict, and cultural memory. It stands as a testament to the architects who dared to uphold their design principles amidst political pressures, ultimately leaving behind a rich architectural legacy that continues to captivate us today.

Acknowledgements

A special note of appreciation to Magdalena Baranowska for granting permission to use her photographs showing in this blog post:

Images 1-4: Warsaw Housing Cooperative at Kole by Magdalena Baranowska

Image 5: Picasso’s drawing of the Warsaw Mermaid, photo: public domain