THE BUILDING IN PAIN: THE BODY AND ARCHITECTURE IN POST-MODERN CULTURE

Introduction

In the following article, Anthony Vidler, a renowned architectural historian and theorist whose work often illuminates the psychological and cultural dimensions of the built environment, creates a complex picture of architecture as a form that not only shapes physical space but also intervenes deeply in the human experience. Published in the Spring 1990 AA Files of the Architectural Association School of Architecture, he examines how the representation of the body in architecture has changed from ancient times to modern and postmodern times. Vidler argues that despite the apparent abandonment of bodily references in modern architecture, contemporary architects such as Coop Himmelblau, Bernard Tschumi and Daniel Libeskind are once again beginning to incorporate the body into their work - but in a radically new way that marks a break with classical notions of humanism. In this article, Vidler explores the philosophical and cultural implications of these shifts, encouraging a deeper consideration of the relationship between human identity and architectural expression.

By Anthony Vidler

No. 19, Spring 1990AA Files

Published by: Architectural Association School of Architecture

"My body is everywhere: the bomb which destroys my house also damages my body, in so far as the house was already an indication of my body." Jean-Paul Sartre

The idea of the architectural monument as embodiment, incorporating reference to the human body for proportional and figurative authority, was, we are led to believe, abandoned with the collapse of the classical tradition and the birth of a technologically dependent architecture. With the exception of Le Corbusier's vain attempt to establish the Modulor as the basis for measurement and proportion, the long tradition of bodily reference, from Vitruvius, through Alberti, Filarete, Francesco di Giorgio, and Leonardo, seems to have been abandoned. The modernist sensibility was dedicated more to the rational sheltering of the body than to its mathematical inscription or pictorial emulation.

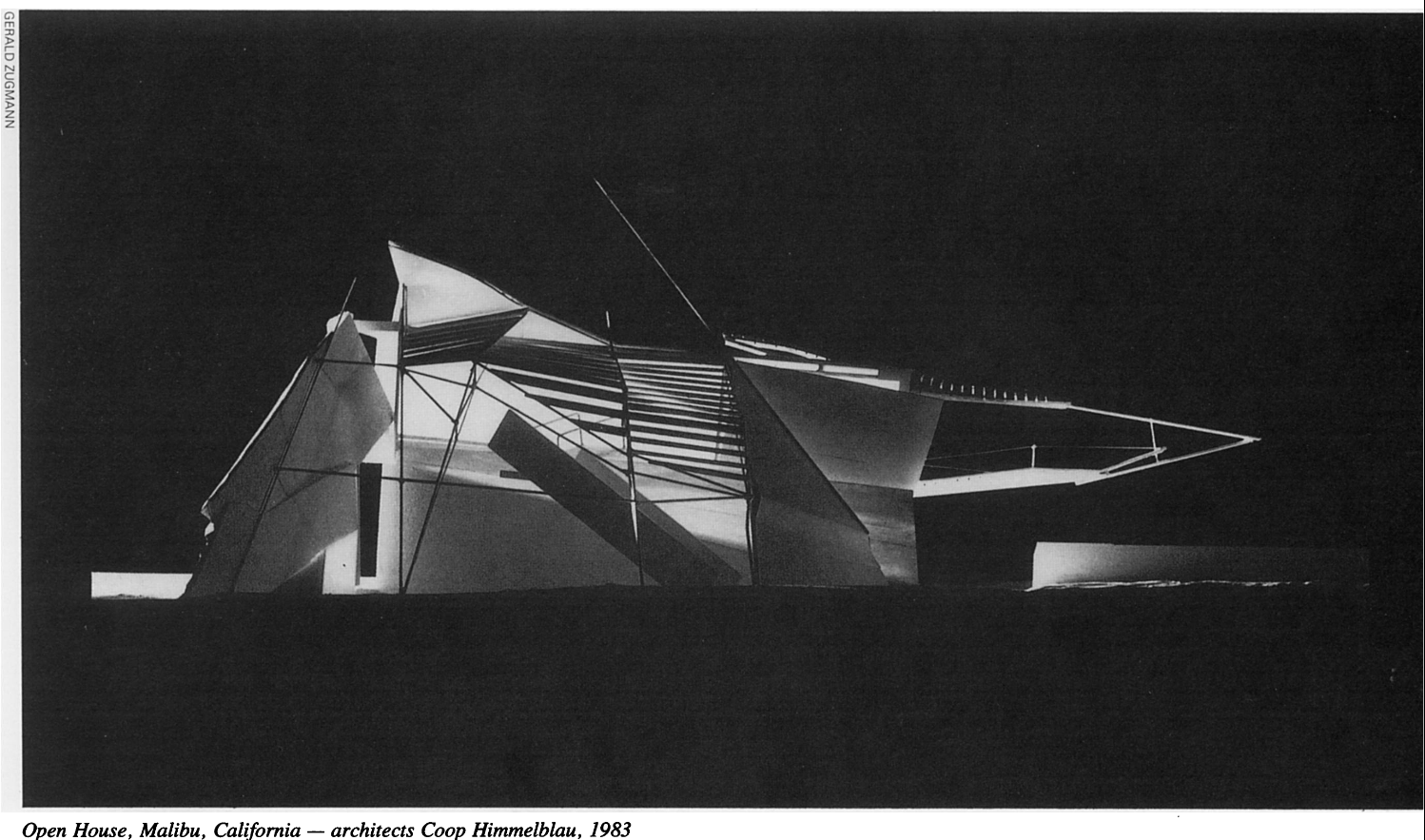

In this context, it is interesting to note a recent return to the bodily analogy. Architects as diverse as Coop Himmelblau, Bernard Tschumi, and Daniel Libeskind are concerned to reinscribe the body in their work. But this renewed appeal to corporeal metaphors is evidently based on a 'body' which is radically different from that at the center of the humanist tradition. It is a body which seems to be fragmented, if not contorted, deliberately torn apart and mutilated almost beyond recognition. Paradoxically, it is advanced precisely as a sign of a radical departure from classical humanism, a fundamental break with theories of architecture that pretend to accommodation and domestic harmony. Evoked as referent and as generator of an architecture that stands against 'Palladian' humanism and Corbusian modernism alike—as Coop Himmelblau has insisted since the late 1960s—this body no longer serves to center, to fix, or to stabilize. Its limits, interior or exterior, seem infinitely ambiguous and extensive; its forms, literal or metaphorical, are no longer confined to the recognizably human, but embrace all of human existence, from the embryonic to the monstrous; its power lies no longer in the model of unity, but in the intimation of the fragmentary, the morsellated, the broken. Within the context of a consumer-oriented historicism, this aggressive and uncompromising delineation of what we might call the posthumanist body has taken on the allure of the 'pure and hard' last stand, a final gesture against the too easily embraced 'return', in the form of commercial post-modernism, to the simulacra of classicism.

On first inspection, this fragmentation of the architectural body might appear to be no more than a simple reversal of tradition, an almost too literal transcription of the idea of dismembering classicism. But, on another level, the examination of the diverse sources of this new bodily analogy in existentialism, Lacanian analysis, and post-structuralist criticism, and an analysis of its relation to previous 'embodiments', from the Renaissance to modernism, demonstrates a more complex theoretical process than that of simple pictorial caricature. Following the long history of the anthropomorphic analogy, these projects exhibit all the traces of their origins in classical and functional theory, while at the same time constituting an entirely different sensibility.

The history of the body in architecture, from Vitruvius to the present, might in one sense be described as the progressive distancing of the body from the building, a gradual extension of the anthropomorphic analogy into wider and wider domains, leading insensibly but inexorably to the final 'loss' of the body as an authoritative foundation for architecture. Three stages in this successive transformation of bodily projection seem especially important for contemporary theory: the building as body; the building epitomizing bodily states or, more importantly, states of mind based on bodily sensation; the environment as a whole endowed with bodily, or at least organic, characteristics. For the purposes of this argument, these moments may, in turn, be roughly identified with historical periods, although, as I shall argue later, this chronological 'progression' is more useful for the sake of clarity than it is historically accurate.

In Vitruvian and Renaissance theory, the body is directly projected onto the building, which both stands for it and represents its ideal perfection. The building derives its authority, proportional and compositional, from the body; in a complementary way, the building acts to confirm and establish the body — individual and social — in the world.

Remember the formulations of Vitruvius, as he traced the origins of proportion to the Greek canons of bodily mathematics, incorporated by the architect-sculptor into the column and into the relations of the different parts of the Order to the whole, and thence into the building, a principle of unity described by the celebrated figure of a man with arms outstretched, inscribed within a square and a circle, navel at the centre, as the guide to perfect proportion. Renaissance theorists, from Alberti to Francesco di Giorgio, Filarete and Leonardo, subscribed to this analogy, which guided all attempts to develop a theory of unity, and determined the search for centralization in all its aspects. For them, buildings were veritable bodies — temples the most perfect of them all, as were cities, the seat of the body social and politic. This organic analogy, indeed, was more than a mere analogy: through figural expression (anthropomorphic form, from the column to the plan and façade) and through embodied geometries, buildings were, in a real sense, bodies; abstract and without the animism of a human form, but bodies nevertheless. Alberti’s proposition that ‘the building is in its entirety like a body composed of its parts’ — part to whole leading to his celebrated definition of beauty as the state where nothing can be added or taken away without destroying this delicate balance between part and whole — was extended to embrace all animate bodies: ‘the parts of buildings should be arranged similarly to those of an animal; as is seen, for example, in the case of the horse, whose parts are equally beautiful and efficient’.

Francesco di Giorgio followed the lead of Alberti and Vitruvius, stating that ‘basilicas have the shape and dimension of the human body’; similarly the city: ‘cities having the qualities, the dimensions and the shape of the human body’. His drawings showed a figure literally superimposed on the plan of a cathedral and that of a city, with the navel at the point of the main square. To plan a city, following Vitruvius, he proposed that one should stretch out a body on the floor, fix a thread to its navel, and trace a circle. This posed the analogy not only in terms of proportional correspondences but of shape. Filarete took the idea even further: the body ‘contains cavities, entrances and deep spaces which lead to its proper functioning’, and in the same way the building has orifices in the form of doors and windows. As the building, so the city: ‘Just like the eyes, ears, nose, mouth, veins, and viscera, the organs are arranged in and around the body as a function of its needs and necessities; one should do likewise in cities.’ Furthermore, like a body, buildings and cities may fall ill: a building can, he hazarded, ‘become sick and die; sometimes it is cured from its illness by a good physician. . . . A number of times it can recover, thanks to a good physician, until its death at its allotted hour. A few are never ill and suddenly die: others are killed by men for some reason or another.’

In an even more extraordinary metaphor, which seems somewhat far-fetched unless we understand the full force of the analogy, Filarete joins this understanding of the death of a building to its birth, and to that which gives it life, its architect-progenitor. In Filarete’s terms, the architect is the ‘mother’ of the building. Before ‘giving birth’ to it, he must dream of it, mentally examining it from all angles, exactly like a woman carries a child in her body; as soon as the building is born, the architect becomes its mother. ‘The newborn baby is the model who will soon be provided with a nurse and a tutor — masons and workers.’ As the building ‘grows’, the architect must contemplate it with satisfaction, ‘because the act of building is none other than a voluptuous pleasure comparable to that of a man in love.’

The power of these formulations lasted, in the classical tradition, until the end of the eighteenth century and, within the enclave of the École des Beaux-Arts, even longer. The body, its balance, standards of proportion, symmetry, and functioning mingling elegance and strength, was the foundation myth of building. As Geoffrey Scott noted in 1914, in The Architecture of Humanism, ‘The centre of that architecture was the human body; its method, to transcribe in stone the body’s favourable states; and the moods of the spirit took visible shape along its borders, power and laughter, strength and terror and calm.’

In this sense, the classical tradition of embodiment corresponds to that primary mode of bodily projection described by Freud in terms of object-surrogates. Here, an object is invested with organic properties that allow it to become a surrogate, stand-in, or function of the body. Normally, this projection is accomplished by describing objects in terms of specific parts of the body. Freud gave the examples of the eyeglass, microscope, telescope or camera, which, in their optical roles, stand in for the eye. Similarly, skyscrapers and obelisks are substitutes for the penis, and dwelling-places and shelters are substitutes for the womb. In a more mechanical analogy, the heart is often compared to a pump, the nervous system to an electrical circuit, the neuronal system to a computer; all these could be unconscious or conscious examples of this form of ‘literal’ substitution and projection.

But during the modern period, and beginning in the eighteenth century, there emerged a second and more extended form of bodily projection in architecture, initially defined by the aesthetics of the sublime. Here, the building no longer simply represented the whole or a part of the body, but was seen as objectifying the various states of the body, physical and mental. Edmund Burke, followed by Kant and the Romantics, described buildings not so much in terms of their fixed attributes of beauty, but rather in terms of their capacity to evoke emotions of terror and fear. Elaine Scarry, in her recently published study The Body in Pain, has described this process as the identification of ‘bodily capacities and needs’ in the object, more general than the ‘concrete shape or mechanism of a specifiable body part’. This mode of projection would include the expressions of mind, spirit, movement — that is, projection in terms of attributes rather than parts, an amplification rather than a simple replication of bodily experience. Thus the phallus and the womb would become generalized attributes of desire. A projection that insists on attributes would lend itself to an exploration of the nature of projection itself: one attribute of the human being, beyond the attributes of ‘seeing, moving, breathing, hearing, hungering, desiring, working, self-replicating, remembering, blood-pumping’, is that as a whole ‘he is therefore a projecting creature’. This would be expressed, not in terms of a specific attribute (vision as the lens of the eye literally projected into space), but by the entire body turned inside out and projected outward, a displacement of the unseen interior state on to an inanimate external object, thereby endowing this object with some sense of response, of animation, to phenomena demanding to be shared.

In architectural terms, the sensibility to the object as mirroring the states, rather than the aspect, of the body was theorized for the first time in the psychology of empathy which emerged during the late nineteenth century. Thus the art historian Wölfflin, seeking to determine the change in style from the Renaissance to the baroque, following his thesis of 1886, ‘Prolegomena to a Psychology of Architecture’, applied the new discipline of psychology to reintroduce the body into the argument, but now in an active and entirely transformed manner:

We judge every object by analogy with our own bodies. The object — even if completely dissimilar to ourselves — will not only transform itself immediately into a creature, with head and foot, back and front; and not only are we convinced that this creature must feel ill at ease if it does not stand upright and seems about to fall over, but we go so far as to experience, to a highly sensitive degree, the spiritual condition and contentment or discontent expressed by any configuration, however different from ourselves. We can comprehend the dumb, imprisoned existence of a bulky, memberless, amorphous conglomeration, heavy and immovable, as easily as the fine and clear disposition of something delicate and lightly articulated.

What had previously been fundamental to classical design theory, a principle of making as well as a standard of judgement, was now entirely placed in the service of perception, and that of objects which, in the classical sense, were not in any way beautiful; the qualities of the architectural object, no matter what the intentions of its makers, were now those of all inanimate nature: only to be understood by a process of projection. ‘We always’, continued Wölfflin, ‘project a corporeal state conforming to our own; we interpret the whole outside world according to the expressive system with which we have become familiar through our own bodies’. This transference of bodily attributes, such as ‘severe strictness’, taut self-discipline’, or ‘uncontrolled heavy relaxation’, takes its place within a ‘process of unconscious endowment of animation’, as Wölfflin calls it; architecture, as an ‘art of corporeal masses’, relates to man as a corporeal being.

Inevitably, in Wölfflin’s scheme, this process is given a historical dimension. There is, he claims, a ‘Gothic deportment’, with ‘tense muscles and precise movements’, which, together with the Gothic nose, ‘which is sharp and thin’, endows Gothic architecture with its quality of sharpness, its precisely pointed forms without relaxation or flabbiness — ‘the body sublimates itself completely in energy’. Similarly, the Renaissance liberates these hard, frozen forms to express a state of well-being, vigorous and animated. In contrast, the baroque manifests itself in weight, the slender bodies of the Renaissance replaced ‘by massive bodies, large, awkward, with bulging muscles and swirling draperies’. Light-heartedness has given way to heaviness, flesh is softer and flabbier, limbs are not mobile, but imprisoned. Movement becomes less articulated, but faster and more agitated, in dances of restless despair or wild ecstasy. And so with architecture, the violence of which is best expressed in Michelangelo’s terribilità. Quoting Anton Springer, Wölfflin notes the combination of ‘mute massiveness’ and unevenly distributed vitality in the sculptor’s ‘unresisting victims of inner compulsion’. Beyond this, indeed, the baroque moves away from the point at which it can even be seen in terms of the human body, or at least in terms of the articulated body invented by the Renaissance. Image, non-corporeal and atmospheric, has replaced defined plastic form, in a counter-reformation dominated by yearning and spiritual ecstasy. Here Wölfflin stops, but not before he has himself projected this baroque spirit well into the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries:

Carl Justi’s description of Piranesi as a ‘modern, passionate nature’, whose ‘sphere is the infinite, the mystery of the sublime, of space, of energy,’ has a more general application. One can hardly fail to recognise the affinity that our own age in particular bears to the Italian baroque. A Richard Wagner appeals to the same emotions. . . . His conception of art shows a complete correspondence with those of the baroque.

Sensible of the lost Renaissance body, Wölfflin, for all the neutrality of most of his work, did insist that in architecture there were limits, whereas in music there were none; the ‘restraining of the finished and rhythmic phrase, the strict systematic construction and the transparently clear articulation which may be fitting and even necessary to express a mood in music, signify in architecture that its natural limits have been transgressed.’ Wölfflin’s message is clear: the sublime in architecture, which necessitates ‘half-closed eyes’ that see lines more vaguely, in favour of unlimited space and the ‘elusive magic of light’, signals the end of bodily projection in its formed and bounded character, and perhaps the end of architecture itself — a dangerous moment from which architecture must draw back.

For the modernists, of course, it was a moment of opportunities, allowing for a universalizing abstraction and a psychology of sensation and movement, epitomized in architecture that mirrored all the states of a regenerated and healthy body, but also corresponded to a similarly healthy mind. Cubist and post-cubist attempts to dismember the classical body in order to develop an expressive model of movement were thus dedicated, not so much to its eradication, but to its re-formulation in modern terms. From Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase (1912), based on Etienne-Jules Marey’s careful studies of movement, to Balla’s Woman with a Dog on a Leash (1912), there seems to be no fear that the body is entirely lost: rather, the question is one of representing a higher order of truth to perception of movement, forces and repose. Even in that ‘primal scene’, the ‘Overture’ to Proust’s Remembrance of Things Past, where Marcel, on awakening, figures the parts of his body according to their successive positions during the night, as if seen on a bioscope — the instrument invented by Muybridge to analyse the running positions of the horse, even this fragmented body is ready at any instant to be recomposed, as Proust observes, into the ‘original components’ of the ego. Analytical science, for many avant-garde modernists, was the necessary and prophetic armature of a new awareness, but not a total loss of the body. Le Corbusier, as we know, even tried to restate it in a newer and more fundamental way, balanced between sensation and proportion — the promenade architecturale and the Modulor — and the plan of the Ville Radieuse unabashedly re-creates Vitruvian man for the twentieth century.

With this sense of the city as a bodily organism, one that is deeply embedded in the classical tradition, we might identify a third and final extension of the body: animism.

Elaine Scarry explains this in terms of the need to diminish the inanimateness of the external world, by projecting a generalized sense of ‘aliveness’, or ‘awareness of aliveness’, on to objects. This form of animism, one that is not confined to the beliefs of old myth- ologies or religions, embraces all the artefacts of civilization. It might be described as an attempt to make an insentient and unre- sponsive external reality feeling and responsible, by endowing it with human attributes. Thus a chair is made into the objectification of human awareness, as in the formulation the ‘chair is the shape of perceived discomfort wished gone’. The chair’s responsibility to- wards humanity has thereby increased; as with the door that is not so irrationally kicked if it pinches the fingers, the chair might be ‘uncomfortable’, which, of course, does not mean that the chair itself experiences discomfort, but that the person sitting in it does.

The three-stage model of projection that I have outlined in the context of its architectural applications over history might also be recognized as an atemporal model for all such embodiments of the external world. Scarry sees it as a gradually expanding field of animism. Take the case of the chair: as a body part, the chair is mimetic of the spine; as a projection of physical attributes, it is mimetic of body weight; as a repository of the desire to will an end to discomfort, it is mimetic of sentient awareness as a whole. Each of these three stages progressively interiorizes the body:

To conceive of the body as parts, shapes and mechanisms is to conceive of it from the outside: though the body contains pump and lens, ‘pumpness’ and ‘lensness’ are not part of the felt experience of being a sentient being. To instead conceive of the body in terms of capacities and needs (not now ‘lens but ‘seeing’, not now ‘pump’ but ‘having a beating heart’ or, more specifically ‘desiring’ or ‘fearing’) is to move further in toward the interior of felt experi- ence. To, finally, conceive of the body as ‘aliveness’ or ‘awareness of aliveness’ is to reside at last within the felt-experience of sentience.

But while, as we have seen, it is easy to find examples of each of these three stages of bodily projection in architecture, and perhaps, strictly speaking, all three modes have always operated in the world, I have chosen to outline the schema historically, following the way in which successive epochs have theorized their manner of embodiment, for a particular, historical, reason. At the same time as we can trace a continuity and a gradual extension of the meta- phor, from the corporeal to the psychological, so we can also detect, starting in the early nineteenth century, but emerging with greatest force in the later years of the twentieth, a decided sense of loss, a lack, stemming from the move away from the archaic, almost tactile, projection of the body in all of its biological force.

This perceived ‘loss’ of the body began, as we have noted, with the Romantic sublime. Under the influence of Kant and the German Romantics, it became the stimulus for a vision of a lost bodily unity fragmented by time and sense experience. The body became an object of nostalgia rather than a model of harmony. In art and criticism it was manifested more as a series of unreconcilable fragments, for example the ‘parts’ that, in Mary Shelley’s story of Frankenstein, never could be assembled into anything but a monster; similar retellings of classical myths of the ideal bodies of Pygmalion and Galatea, of Apelles and Protogenes, and new stories of the creation of the unknown ‘monstrous’ double of man in art (such as Balzac’s short story ‘Le Chef-d’ oeuvre inconnu’), reinforced the Romantic tragic sense of loss.

Such fragmentation was given its psychoanalytical explanation by Jacques Lacan, who in his classic essay of the late 1930s, ‘The Mirror Stage’, proposed the model of a pre-mirror-stage body, a ‘corps morcelé’, or, literally, a morsellated body that, at the moment of the mirror-stage, participated in a sort of drama impelled towards a spatial identification of the self with regard to its reflection. In this model the mirror is construed as a lure that machines the fragmented phantasms of the pre-narcissistic body into what Lacan calls ‘a form that [is] orthopaedic of its totality’. Deprived of its previous status by the reflection of the whole, this morsellated body is repressed to the unconscious, showing itself regularly in dreams, when the motion of the analysis touches a certain level of the aggressive disintegration of the individual:

It appears then in the form of disjointed members and of organs figured in exoscopy . . . that have for ever been fixed by the painting of the visionary Jerome Bosch. But this form reveals itself as tangible on the organic level itself, in the fragile lines that define a fantasmic anatomy, manifest in the symptoms of schizophrenia, or of spasm, of hysteria.

Lacan’s structuralist notion of a repressed fragmentation of the body finds its post-structuralist analogue in Roland Barthes’s ‘Fragments of a Lover’s Discourse’, in which he describes a body that, subjected to the gaze of desire, is, so to speak, transformed into a corpse; the very look, or gaze, of a hypothetical lover, projected on to the body of the sleeping loved one, is as analytical and dissecting as that of a surgeon in an anatomy class. Like Proust (Marcel) watching Albertine asleep, the watcher searches, scrutinizes, takes the body apart, as if to find out what is inside it, ‘as if the mechanical cause of my desire were in the adverse body’; ‘certain parts of the body are particularly appropriate to this observation: eyelashes, nails, roots of the hair, the incomplete objects.’ This process, Barthes observes, would be the opposite of desire, and rather like ‘fetishizing a corpse’. He illustrates it by reference to Sarrasine, Balzac’s Romantic version of the Pygmalion myth. The central character, Sarrasine, falls in love with the transvestite singer La Zambinella. Before seeing La Zambinella, he has loved only ‘fragmented woman’ — ‘divided, anatomized, she is merely a kind of dictionary of fetish objects. This sundered, dissected body (one is reminded of boys’ games at school) is reassembled by the artist (and this is the meaning of his vocation) into a whole body . . . in which fetishism is abolished and by which Sarrasine is cured.’ A ‘unity’ discovered in ‘amazement’, this body will of course be returned to its previous fetishized state when Sarrasine realizes the trick that his projected desire has played on him. Barthes remarks on the list of anatomical details that make up La Zambinella’s body — a ‘monotonous inventory of parts’ that leads to the crumbling of what is being described: ‘language undoes the body, returns it to the fetish’.

In a first instance, the body is almost literally placed in question. Confronting the architecture of Himmelblau, or, less dramatically, of Tschumi, the owner of a conventional body is undeniably threatened, as the reciprocal distortions and absences which are felt in response to the reflected projection of bodily empathy operate almost viscerally on the body. We are contorted, racked, cut, wounded, dissected and intestinally revealed, impaled and immolated; we are suspended in a state of vertigo, or thrust into a confusion between belief and perception.

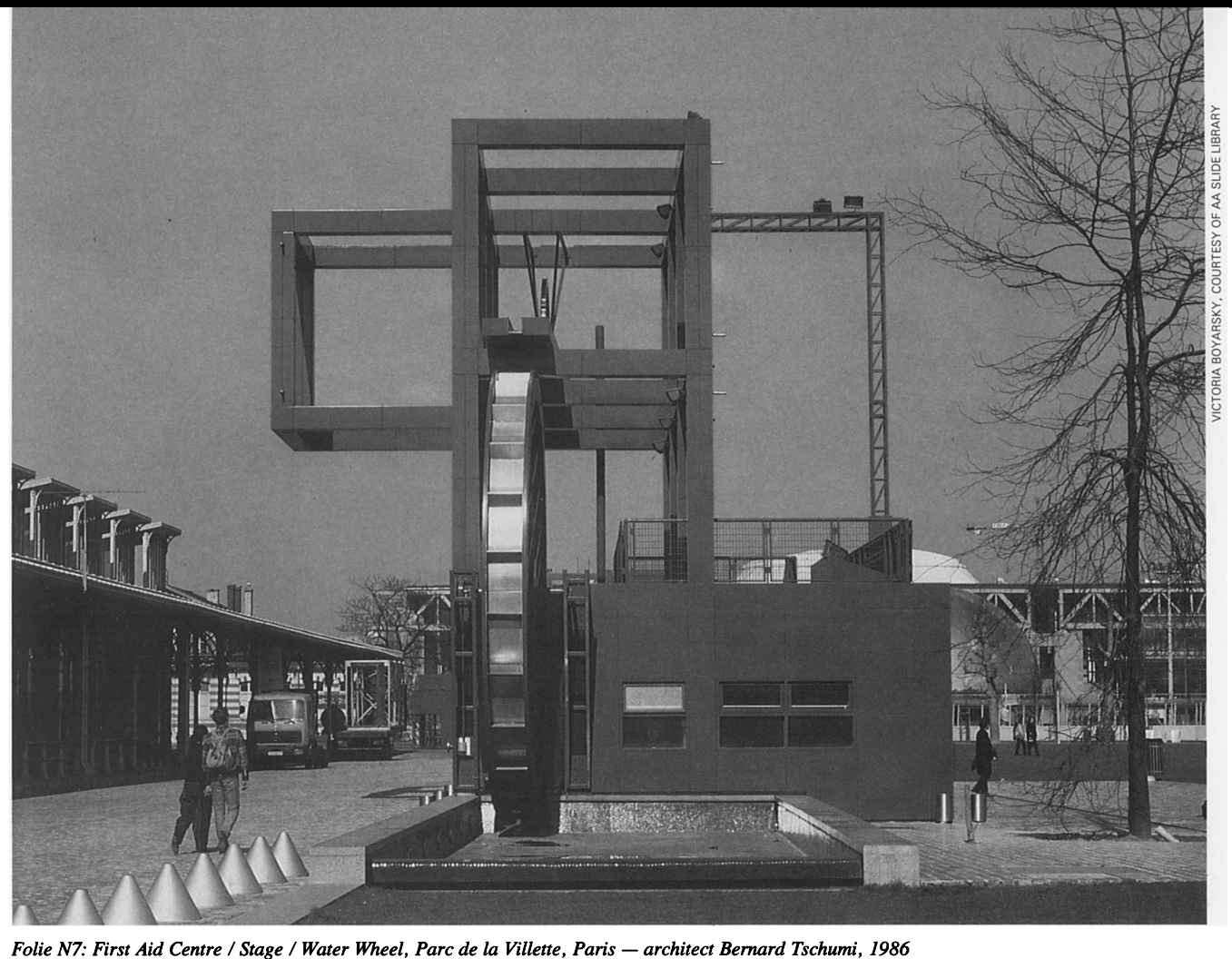

But this active denial of the body takes on, in the post-modern world, the aspect of an auto-critique of a modernism that posited a quasi-scientific, propaedeutic role for architecture. The example of the follies designed by Bernard Tschumi at Parc de la Villette is instructive. Self-consciously echoing the dynamic and twisting forms of Constructivism, a movement dedicated to the inscription of a new revolutionary body in form, Tschumi’s follies in fact propose an entirely different sensibility. While each notational system developed by the avant-garde was dedicated to the reinscription of the (modernist) body in architecture, with every arrow, moving form or architectural element disposed to promulgate health, the notations of Tschumi eschew such utopian ends. Where the upward spiralling ramps of the Tatlin tower stood, at one level, for the endless and regenerative callisthenics of the new society, the follies of La Villette presuppose no therapeutic ends. Analogically, the folly stands for a body already conditioned to the terms of dissemination, fragmentation and interior collapse. Implied in every one of his notations of a space or an object is a body without a centre, in a state of self-acknowledged dispersion and unable to respond to any prosthetic centre fabricated by architecture. The body is not, as in modernist utopia, to be made whole through healthy activity; no avant-garde aerobics can save it from decay. Rather, it has finally recognized itself as an object whose finitude is ever in question, and whose powers are in doubtful play, always to be tested by the infiltration of other objects. Thus the fragmented bodies in movement of The Manhattan Transcripts find their always provisional resolution in La Villette or Tokyo: the filmic fragmentation of bodily unity finds its architectural complement in the fragmentation of architectural unity seeming to aspire to the exhaustion of corporeality itself. While inhabitation of some kind or another is expressed in every element, ramp, stair or balcony, the potentially occupying body receives no comforting organic referent, but is every moment experienced through anti-bodily states, such as vertigo, sudden vertical and sideways movements, and even potential dissection. The functional analogies of modernism theorized the building as a ‘machine for living in’, with the implication that a smoothly running machine, tailored to the body’s needs, was modernity’s answer to the proportional and spatial analogies of humanism. Tschumi’s machine-like structures have rejected their assumed contents, and have been exploded so that all questions of maintenance, repair or even working are suspended. With no need to run smoothly any more, and without the necessity of responding to real bodies, they are complete in themselves, free to play endlessly in space.

These objects of post-modern bodily projection, however, by their nature refuse any one-to-one ascription of body and building. Their calculated effects are devised to extend far beyond actual identification with specific body parts or whole bodies; rather, they are seen like machines for the generation of a whole range of psychological responses that depend on our faculty of projecting on to objects states of mind and body — Scarry’s second level of bodily projection. ‘We want . . . architecture that bleeds, that exhausts, that whirls and even breaks’, claimed Himmelblau in 1968. ‘A cavernous, burning, sweet, hard, angular, brutal, round, delicate, coloured, obscene, voluptuous, dreaming, seductive, repulsive, wet, dry, palpitating architecture. An architecture alive or dead. Cold, cold as a block of ice. Hot, hot as a burning wind.’ This uncomfortable body was subsequently stretched to include the entire city. ‘The Skin of this City’ (Berlin, 1982) proposed a form whose ‘horizontal structure is a wall of nerves from which all the layers of urban skin have been peeled away’.

Such a literal biomorphism, akin to many similar but less threatening science-fiction images of the era of Archigram, has in recent years been extended by the architect-creator’s desire to merge his body completely with the design and its context. In a revealing interview with Alvin Boyarsky, Himmelblau have described their design experiments as a kind of automatic writing that, operating through blind gesture translated into line and three-dimensional form, literally inscribed the body-language of the designer on to the map of the city.

Photographic collages of Himmelblau’s portraits, merged by reproductive processes into the texture of city plans, dramatically illustrate the urge to dissolve the authoritarian body of the architect with the world that receives its designs. In this Veruschka-like procedure, much in the same way that Cindy Sherman has developed her own self-portraits buried in garbage-filled soil, Himmelblau oscillate between narcissism and its opposite, in a strangely powerful celebration of the will to lose power.

But these deliberately aggressive expressions of the post-modern corporeal also operate in another register, that of the strangeness evoked by — as Freud noted with regard to the feeling of the uncanny — the apparent ‘return’ of something (the body) presumed lost, but now evidently active in the work. Freud identified two causes of the uncanny, both founded on the movement between prior repression and unexpected return. The first stems from the return of something that was thought to be definitively repressed, such as ideas of animism, magic, totemism and the like. Once they have ceased to be believed in as real, they throw into doubt the status of reality when they recur, putting material reality into question. Examples of such a form of the uncanny would be the return of the infantile belief in the omnipotence of thoughts — coincidence leading to the fear that one has killed a person after speaking idly of his death — or the seeming return of magic properties to a thing long since divested of its magical significance. Freud recounts having read a story in The Strand Magazine, in which a house furnished with a table carved with crocodiles is the setting for a night of faint terror, when smells and forms begin to move through the rooms, as if some ghostly crocodiles were haunting the place. The second stems from the return of repressed infantile complexes, for example castration or womb fantasies. These, on returning, throw into question not so much the status of reality — such complexes never were thought to be real — but rather the status of psychical reality. Freud gives as an example of such causes ‘dismembered limbs, a severed head, a hand cut off at the wrist... feet which dance by themselves’, evidently uncanny because of their proximity to the castration complex. In the face of Himmelblau’s constructions, there is a strong temptation to ascribe our sense of destabilization to such an uncanny, now embodied in the dancing forms of a building once a body.

Such an interpretation is reinforced by Himmelblau’s own opposition to the domestic, the Heimlich, in any form. Their passionate appeal, expressed in explosive projects and performances, for a deliberately non-accommodating architecture has been tied, from the outset, to a resolute refusal of domesticity. ‘Our architecture is not domesticated’, they stated in 1982; ‘it moves around in urban areas like a panther in the jungle. In a museum it is like a wild animal in a cage.’ Thence, in the exhibit Architecture is Now, installed at Stuttgart in 1982, the beam that, like a backbone and head, rises and sinks like a panther. This animal-like play, perhaps a recasting in terror of Alberti’s benign vision of a ‘building like a horse’, was at the same time allied to an exploration of that more elusive manifestation of the anti-domestic, the uncanny — das Unheimliche. The haunting absence of the body became as much a preoccupation as its physical presence, notably in the Red Angel Bar in Vienna of 1980: who knows, Himmelblau asked, what an angel really looks like. They cited Melville, who wrote in Moby Dick of the wind that had no body: ‘all the things that most exasperate and outrage mortal man, all these things are bodiless, but only bodiless as objects, not as agents.’ The bodiless object and the bodily agent, modelled in steel and wire, here play together in a literally cutting fantasy. Finally, the Hot Flat, Vienna, 1978, a ‘permanent’ monument to an architecture that burns, or the Haus Meier-Hahn, Dusseldorf, 1980, otherwise titled Vector II, with its impaled roof, illustrate almost too directly, but uncomfortably enough, the will to destroy the house of classical architecture and the society it serves. The latter project, indeed, encapsulates didactically, if not archi-tecturally, the twin ambitions of Himmelblau to drive a stake through both the house and the specifically humanist body it represents.

This didactic and dramatic example of the house impaled takes its place, in the post-war period, within that discourse which is concerned to reveal the existential limits of what Gaston Bachelard has termed ‘the coefficient of adversity’. This calculus of threat was explored by Sartre in Being and Nothingness, written in the aftermath of the war, in which the definition of the self and its body is described as a function of the perception of resistance that objects in the world have to the self. Thus, ‘the bolt is revealed as too big to be screwed into the nut; the pedestal too fragile to support the weight which I want to hold up, the stone too heavy to be lifted up to the top of the wall.’ In other cases, objects threaten an established instrumental complex — the storm the harvest, the fire the house. Step by step, these threats extend to the centre of reference indicated by all these instruments; this centre in turn indicates the centre of reference to them. Thence the central proposition with regard to the body: the body is indicated, first, by an instrumental complex and, second, by a threat posed within this context:

I live my body in danger as regards menacing machines as for manageable instruments. My body is everywhere: the bomb which destroys my house also damages my body in so far as the house has already an indication of my body. This is why my body always extends across the tool which it utilizes: it is at the end of the cane on which I lean and against the earth; it is at the end of the telescope which shows me the stars; it is on the chair, in the whole house; for it is my adaptation to these tools.

In this way Sartre rejects the classical notion of embodiment which then projects itself on to the external environment as a mode of apprehending or controlling it. Instead, he poses our original relation to the world as the foundation of the revelation of the body; ‘far from the body being first for us and revealing things to us. It is the instrumental-things which in their original appearance indicate our body to us. . . . The body’, he concludes, ‘is not a screen between things and ourselves; it manifests only the individuality and the contingency of our original relation to instrumental-things.

Here, our initial recognition of Sartre’s formulation of the ‘body in the house’ as resonating with all the power of a long classical tradition, a tradition that posed the body as the essential model for all other created instruments, the body as, a priori, a foundation for the recognition and apprehension of all other objects, suffers a defeat. Sartre’s body participates in a world within which it has to be immersed and to which it has to be subjected even before it can recognize itself as a body. It knows itself precisely because it is defined in relation to complexes of instruments that themselves are threatened by other instruments, understood as ‘destructive devices’. The body knows itself to exist by experiencing a ‘coefficient of adversity’. Thus, where in classical theory since Alberti the house is a good house only in so far as it is constituted analogically to the body, and the city a good city for the same reasons, in Sartrean terms the body is seen to exist only by virtue of the existence of the house: ‘it is only in a world that there can be a body’. The bomb that destroys the house does not destroy a model of the body, but the body itself. We are precipitated into a world of absolute danger, and at the same time made to understand that this threat exists only in so far as we are in this world. It is, no doubt, the shiver of this world that Himmelblau wishes us to experience.

Such may be the case; and the staunch radicalism of Himmelblau’s efforts against the architectural system, over ten years, must be recognized. But it must also be noted that the uncanny, and precisely the uncanny that stems from suppressed terror, is evident in the world in more ways than the expressionist forms engendered in the Hot Flat, or, more recently, in the Savage Apartment, Vienna, 1983. Elaine Scarry, perhaps conscious of the all too easy ways in which culture absorbs shock while purportedly displaying its ‘reality’, invokes the uneasy slippage between the polarities of domesticity and terror in her discussion of torture, where she contrasts a normal room, and its extensions into buildings and cities, with a torture chamber. The former, the room, in normal contexts, she claims,

the simplest form of shelter, expresses the most benign potential of human life. It is, on the one hand, an enlargement of the body: it keeps warm and safe the individual it houses in the same way the body encloses and protects the individual within: like the body, its walls put boundaries around the self, preventing undifferentiated contact with the world, yet in its windows and doors, crude versions of the senses, it enables the self to move out into the world and allows that world to enter.

In the latter, the torture chamber, this room is closed, the exits are barred; its benign names — ‘guest room’, ‘safe house’ — belie the annihilation within:

The torture room is not just the setting in which the torture occurs; it is not just the space that happens to house the various instruments. . . . It is itself literally converted into another weapon, into an agent of pain.

Between the room and the torture chamber there seems to be an irrevocable distance; yet any room may be used as a torture chamber, and all rooms may act as prisons for a disturbed psyche. Here all distinctions blur, to be replaced by an understanding of the precarious nature of comfort, the fine line dividing heimlich from unheimlich.

In this lies the resistance of architecture, traditional or not, to being turned into a specific instrument of comfort, reform, revolution or psychical transformation. Himmelblau’s contorted and cruel constructions, Tschumi’s exploded cubes, Libeskind’s interior abysses here take their rightful place beside Marey’s photographs of men in movement and Duchamp’s translations of these analytical diagrams in art; they are expressions of a cultural condition more than they are analyses of it, or even critiques of its fundamental social and political problems. Such expressions may have a salutary effect and, when built, they stand as monuments to a particularly self-conscious and self-representational epoch. But they of themselves will have little power to transcribe their bodily projections back on to society, save perhaps in the inevitable unease that we experience at each moment when we notice the infinite capacity of society to adapt to, and even to delight in, the environments presented it by the architect. Perhaps it was this realization that led John Hedjuk, commenting on Daniel Libeskind’s Chamber Works exhibited at the AA in 1983, to remark, 'This work of Libeskind has turned the body inside out; and here we also have the soul being discarded.